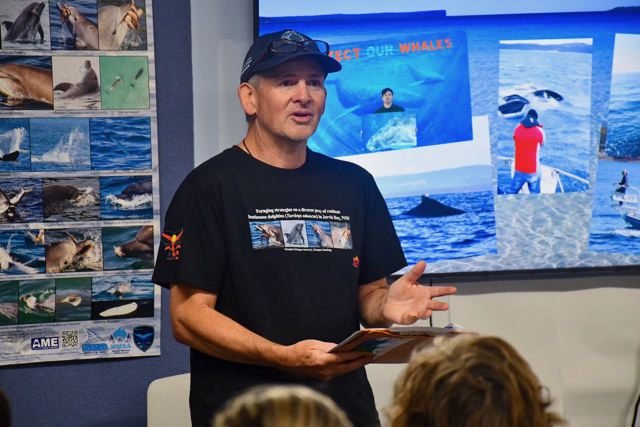

Scott Sheehan divides his time between paid projects and self-funded research work. Photo: Supplied.

As Australia’s east coast humpback whale population recovers, the migration patterns have returned to what they would have been hundreds of years ago.

That is one of the most satisfying observations of Scott Sheehan who has been collecting data on marine mammals for 25 years.

“I started out as a volunteer with Dr Michelle (Lemon) Blewitt doing her PhD on the resident bottlenosed dolphins of Jervis Bay,” Mr Sheehan said. “I was a photographer and field assistant and that was where it all started.”

He studied environmental science and began volunteering on several marine projects up and down the coast. He found work as a marine mammal observer which has taken him all around Australia and New Zealand.

Mr Sheehan strongly recommends volunteering on projects to build a skill set for marine mammal observations. He divides his time between paid projects and self-funded research work and his best experiences have been while volunteering.

He had been collecting data, predominantly on dolphins and whales, from 2000, then started his own research group, Marine Mammal Research (MMR), in 2006. It works with other research groups and university researchers, as well as doing its own independent research. It has published and presents at marine mammal conferences.

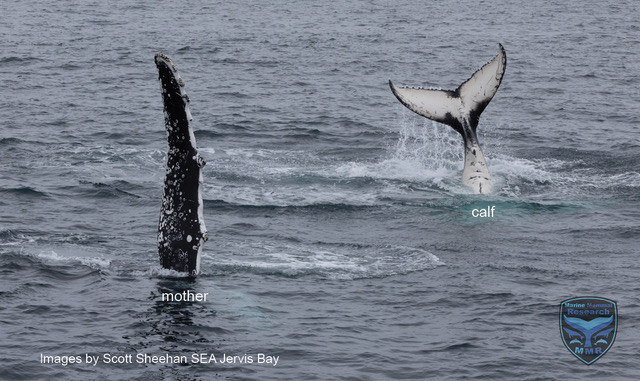

A current focus of Mr Sheehan is the mother and calf humpback whales migrating south.

He is splitting his time between Jervis Bay and Eden where he has been visiting to observe whales since 2006.

READ ALSO: Sparks fly as Eurobodalla Council debates housing strategy, Batemans Bay Master Plan

In October he watched the mothers and calves resting in Jervis Bay then drove to Eden. From that he collected data on how the whales’ activities differed between the two locations, how fast they travelled between the two spots and which other whales they associated with as they travelled.

Typically, calves are born in June and July so are four to five months old when they reach the South Coast.

He is observing maternal calf development – namely mother whales teach their calves how to be whales.

“By breaching or tail slapping, they are activating those skills in the calves as they are fattening them up on a nice long, slow journey,” Mr Sheehan said. “It is getting the calf ready for the cold waters of Antarctica and prepare for the change from mother’s milk to krill. They only have that short period in warmer waters to learn how to be a whale in cold water.”

The whales typically spend December to April feeding on the nutrient-rich krill of Antarctica. They socialise there but do not breed.

The whale’s gestation period is around 11 to 12 months so breeding while in Antarctica would see the calves born in those icy waters a year later. Breeding in the warmer waters ensures the calves are born in a much gentler environment to maximise their chances of survival.

“That is one reason why their numbers are recovering,” Mr Sheehan said.

Historical data estimated that the humpback whale population was as low as 200 but has rebounded to 50,000, according to Dr Wally Franklin’s The Oceania Project.

“Years ago, we never would be whale watching in August, but as the population has increased, they are migrating now like they would have pre-whaling days,” he said. “We are witnessing the population recovering from the whaling days which is amazing.”

Scott Sheehan of Marine Mammal Research helps run citizen science project SEA Jervis Bay. Photo: Supplied.

Mr Sheehan said humpback whales only opportunistically foraged while migrating south, so they lost a lot of weight while undertaking one of the world’s longest migrations.

He said researchers were always learning. “By collecting data over long periods of time we can learn about when and where they turn up, and the different areas they like to rest.”

READ ALSO: New maintenance policy signalled in face of ‘constrained resources’ for regional road upkeep

One highlight of that was capturing site fidelity behaviour.

On 18 October 2008, he got great fluke shots and body shots of a mother whale that identified her as clearly as humans are identified by fingerprints. She returned to the same location on 18 October 2010 with another calf, demonstrating strong site fidelity.

“She came back to the location around the same time,” Mr Sheehan said. “It is like us going on holiday to the same place every year.”

His other focus is SEA Jervis Bay which is a citizen science project.

“We need the general public to be involved and come out with us learning how to contribute to science,” Mr Sheehan said. “Anyone walking along the beach, or surfing or out on boats can document what they see and contribute to science.”