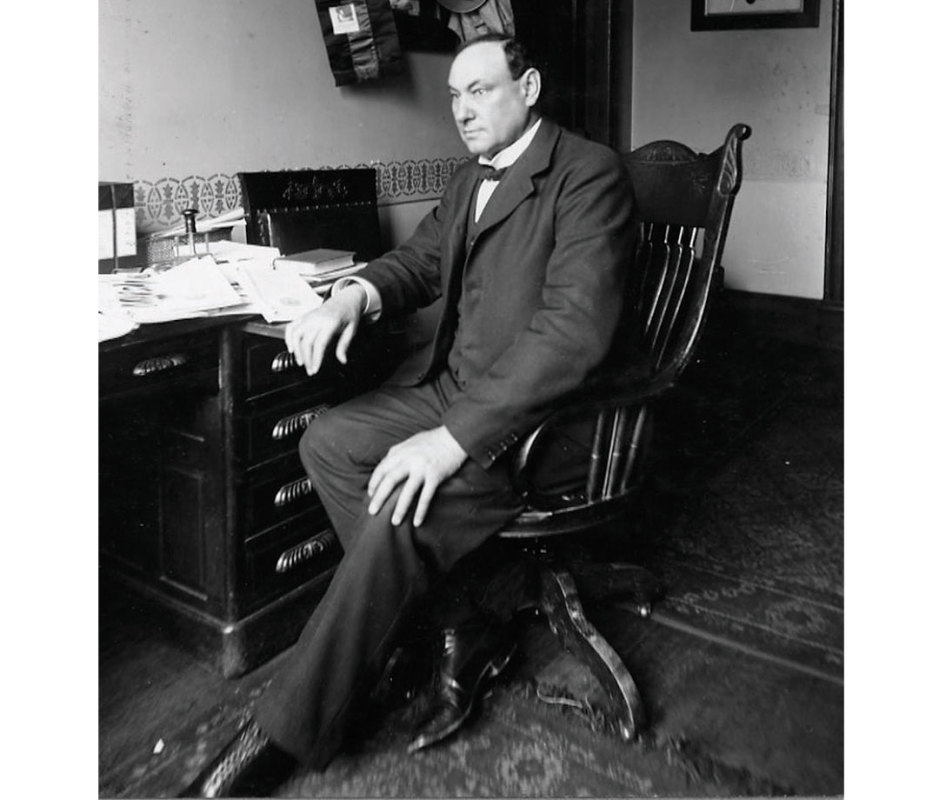

One of whiskey’s unsung champions was Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, chief chemist of the U.S. Department of Agriculture from 1883 to 1912. While his name is largely forgotten now, he is in many ways the father of modern American whiskey, because his beliefs about how it should be produced and labeled are reflected in the regulations that we still follow today.

“He fought impurity, but he also fought dishonesty in labels,” wrote The New York Times when Wiley died in 1930 at the age of 85. “In Pre-Prohibition days, he said that he believed 85 percent of the whiskey sold over bars in this country was adulterated.”

Wiley insisted that the color of the whiskey should come from aging in a barrel and that the whiskey shouldn’t be so distilled or redistilled that it lost all of its innate flavor. He believed above all that whiskey should not be blended with all kinds of additives. One of his chief concerns was keeping as many of the naturally occurring flavor compounds in the whiskey as possible, which at the time was a very contentious opinion.

Courtersy The Gistory Collection/Alamy

Essentially, Wiley’s ideal for whiskey was very similar to our current definition of straight whiskey. But in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Wiley’s opinions were not universally supported. He was forced to wage an aggressive campaign against a number of companies that realized if Wiley was successful, they would have to change their production techniques or label their spirits differently, which would destroy their brands’ reputations.

One of Wiley’s main adversaries was the National Wholesale Liquor Dealers’ Association, which represented many of the rectifiers that wanted the rules around whiskey to be fairly loose. Defining whiskey and ensuring its purity was ever more important because whiskey had suddenly become big business. Just as the demise of the colonial rum market at the close of the 18th century created an opportunity for whiskey distillers, the industry would now get a boost from the misfortune of Cognac. Beginning in the 1860s, a small insect called phylloxera had destroyed a great swath of vineyards in Europe. And without grapes, it’s hard to make Cognac—or wine, for that matter. In the late 1800s this was a huge problem. Cognac was wildly popular and was called for in numerous cocktail recipes.

Whiskey, of course, was more than happy to supply Cognac’s customers. Distillers were thrilled to finally be able to step out of brandy’s shadow and assume a starring role. Some of these brands were already trying to change the perception of American whiskey as a low-quality product by touting its heritage and the excellence of their spirits. These distillers, including Colonel E. H. Taylor, naturally supported Wiley and disapproved of the shenanigans that had long plagued the whiskey industry.

On the other side of the debate were the blenders (also known as rectifiers), who took a decidedly different approach to making whiskey.

“The blender doesn’t care whether the whisky [sic] is made in Kentucky or Indiana or Illinois—nor whether it is made in a log still or a continuous copper still—nor whether it is made from spring water or well water or pond water—nor whether it is run 100 proof or 180 proof,” lamented a piece in Bonfort’s Wine and Spirit Circular in September of 1906.

This was an especially important and topical issue because, at the turn of the century, consumers were incredibly interested in how their food and drinks were being made. The timing was perfect, too, for Upton Sinclair’s bestselling novel TheJungle, which exposed filthy and unsafe practices in the meat industry, was a sensation when it was published in 1906. After years of debate and discussion in the media and in Congress, Wiley was ultimately successful. For his trailblazing work as a chemist to create and uphold standards of pure food and drink, he is often credited as the inspiration and driving force behind the wildly important Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

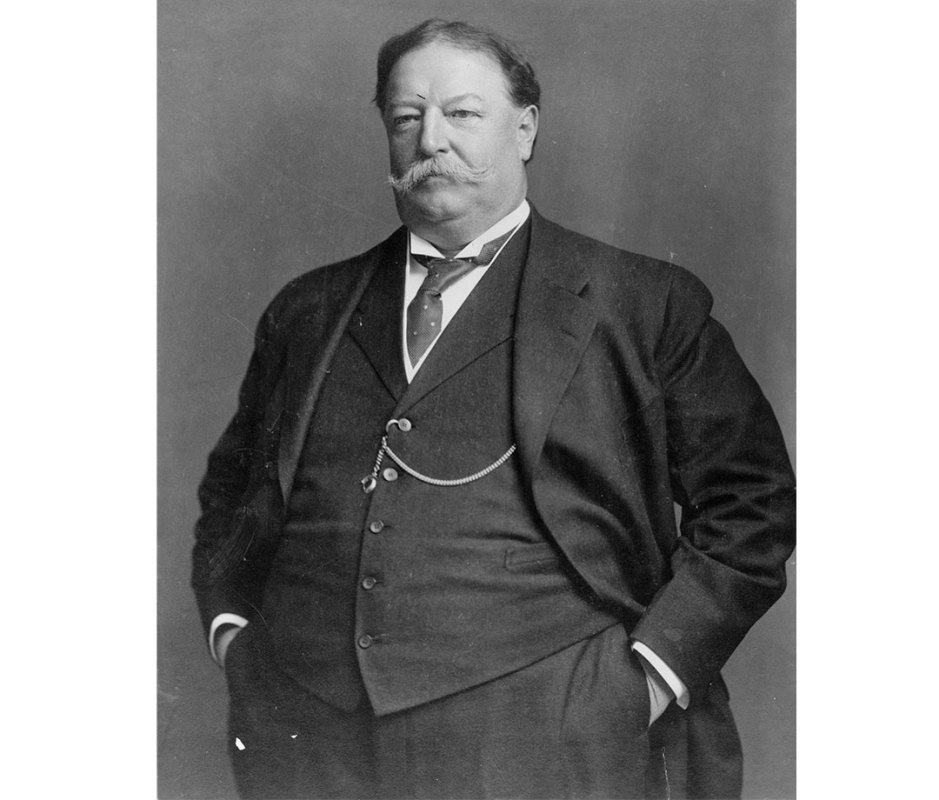

Courtesy MPI/Stringer/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Then, with the support of President Theodore Roosevelt and Attorney General Charles Joseph Bonaparte, Wiley was able to limit the use of the term whiskey to only straight whiskeys. The result was that all the other kinds of whiskey on the market had to be labeled “blended whiskey,” “imitation whiskey,” or “compound whiskey,” which wasn’t exactly great for their sales and served to undermine their credibility and prestige. It’s hard to claim your whiskey is wonderful when it’s called imitation whiskey by the U.S. government

Given that politicians were involved, however, Wiley’s pioneering work would get completely undone. The unraveling came by way of none other than President William Howard Taft, who declared in late December of 1909 that, basically, the term whiskey could be used for a wide range of spirits. Taft did carve out a special class for straight whiskey, but any other kind of whiskey would just have to state what it was made from on its label.

Related: William H. Macy Argues There’s a Right Way to Drink Whiskey: ‘Some People Run Afoul’

Taft’s ruling stated: “The public will be made to know exactly the kind of whisky [sic] they buy and drink. If they desire straight whisky, they can get it by purchasing what is branded ‘straight whisky.’ If they are willing to drink whisky of neutral spirits, then they can buy it under a brand showing it; and if they are content with a blend of flavor made by the mixture of straight whisky and whisky made of neutral spirits, the brand of the blend upon the package will enable them to buy and drink that which they desire.”

Something similar happened in the U.K. that same year. After a Royal Commission was convened and lengthy testimony heard from a wide variety of distillers, the definition that was settled on for the term whisky was disappointingly vague.

Needless to say, Taft completely missed Wiley’s point in establishing standards for whiskey, and perhaps also the larger aim of the Pure Food and Drug Act. (The president did concede that whiskey could not be made from molasses—that was a step too far, he decreed, and was rum.)

Courtesy Workman Publishing

Taft’s ruling naturally upset all the distillers who were making whiskey the old-fashioned way and supported Wiley. The Rohr McHenry Distilling Co. in Wilkes-Barre, PA, even decided to publish copies of the impassioned letter it had sent to President Taft about the dangers of allowing imitation whiskey to be sold, including one that found its way into Harvard’s library.

My favorite line from this screed is: “It is so purely imitation, why not allow the consumer to pay for it with imitation money?”

But there wasn’t much time for Wiley or his opponents to recover from their battle. Whiskey drinkers would soon face an even tougher fight that would nearly destroy the entire industry—Prohibition.

This interview appeared in Men’s Journal’s fall Whiskey Special issue.

Excerpted from The Whiskey Bible by Noah Rothbaum (Workman Publishing). Copyright © 2025.