“Whisky loch” (or “lake”) is a term that arose in the 1980s and ’90s to describe the vast glut of Scotch sitting around in barrels. At the time, few people were interested in old whisky and the same was true in America. Imbibers had migrated to vodka and tequila, leaving brown spirits in their wake. Bourbons and ryes that did make it into bottles idled on liquor store shelves—dusty and unnoticed.

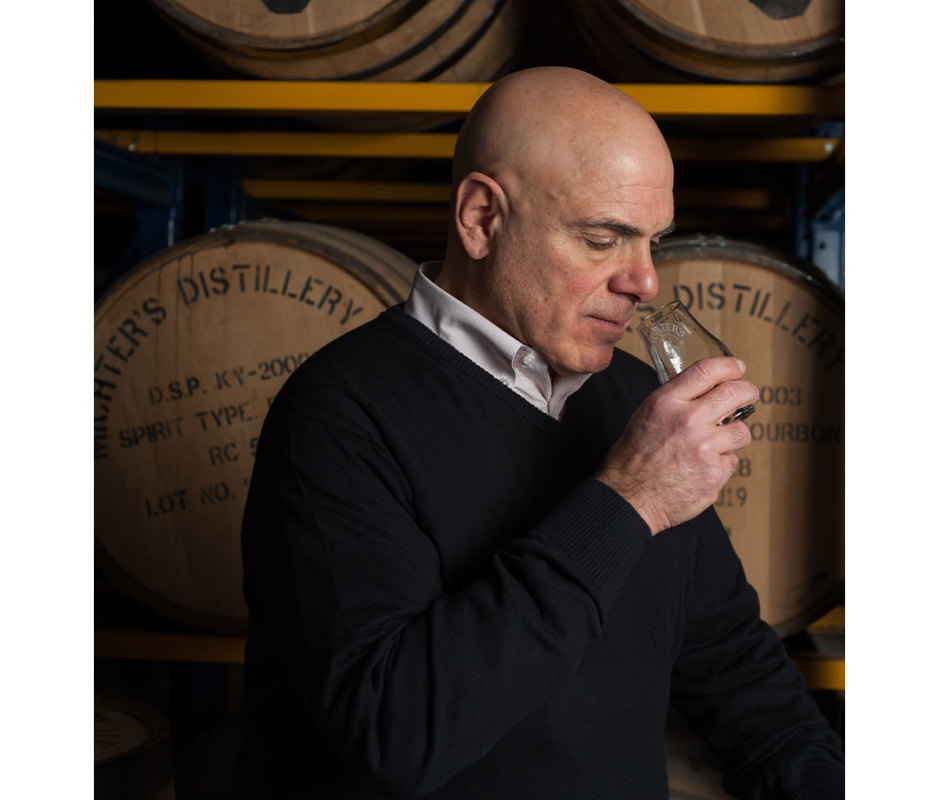

“It was like a fistfight to sell the stuff years ago,” says Joe Magliocco, president of Michter’s Distillery in Louisville, KY.

Magliocco launched Michter’s in the waning days of that first whiskey lake. He saw a gap in the market and suspected a smaller brand could succeed in selling niche products abandoned by the big brands. “There was little to no market for age statement bourbon in those days,” he says, “and there was almost no market for American rye.” But Magliocco believed in the power of reviving a storied brand.

Michter’s is now hitting its stride just as many in the industry believe a second whiskey lake is forming. Supply appears to be outpacing demand again, yet Magliocco remains confident. One way to navigate turbulent waters is to plot a sensible course, trust your judgment, and sail on—no matter the wind and waves.

Courtesy Michter’s Distillery

For nearly three decades, Magliocco has followed a single lodestar: make the “best American whiskey.” And he’s betting that course will carry them across the next whiskey lake.

Michter’s history began in 1753, when Swiss Mennonite brothers John and Michael Shenk set up a still in southeastern Pennsylvania. It was one of hundreds of distilleries that dotted the rural Northeast, where corn and rye were abundant. Distilling proved a sensible way to preserve and ship crops while adding value. Over the next two centuries, the Shenk distillery was bought and sold, went bankrupt twice, and changed names several times.

Related: Best Rye Whiskey Brands to Spice Up a Sazerac, Manhattan, or Old-Fashioned

It became Bomberger’s in the 1800s, was shut down during Prohibition, then, in the 1950s, was bought and revived by Pennco Distillers. The new owner, Louis Forman, renamed the whiskey “Michter’s,” which had a sturdy, historic, Teutonic ring. (In fact, the name was a fabrication—a mashup of Forman’s sons’ names, Michael and Peter.)

Within three decades, Michter’s found itself drowning in that first whiskey lake. Unable to sell its whiskey at a profit, the distillery declared bankruptcy in 1989 and closed for good on Valentine’s Day 1990.

Fast forward to the late 1990s. Magliocco grew up in New York City, graduated from Yale College, and went on to earn a degree at Harvard Law School. During school vacations, he bartended, then worked for a distributor and liked the industry’s prospects. He believed the public’s disinterest in brown spirits was a lull, not a final chapter. He teamed up with Richard Newman, former CEO of Austin, Nichols & Co., Inc. (the creator and original owner of Wild Turkey), with the idea of establishing a brand and eventually building a distillery to make it. In 1997, the pair began acquiring and bottling barrels of widely available surplus aged whiskey while making plans to produce their own outside Louisville.

Courtesy Michter’s Distillery

One of the whiskeys Magliocco was fond of in his early days as a bartender and importer was Michter’s. Along the way, he made a fortuitous discovery: The trademark on the name “Michter’s” had lapsed after the distillery shuttered. He filed the paperwork, and the name was his—for a $245 filing fee.

The brand’s first releases were a 10-year bourbon and a 10-year rye. Sales were under whelming. When Magliocco approached bars and stores, managers would narrow their eyes and ask, “Who the hell wants a 10-year-old rye?”

Undaunted, Michter’s moved to the next phase—working with a third-party distillery to produce whiskey to their own specifications, something Magliocco likened to “borrowing a friend’s kitchen.” In 2012, they finally opened their own distillery, a modern operation on 12 acres in Shively, a Louisville suburb. The company began transitioning from sourced whiskey and borrowed facilities to making its own, controlling every variable.

One key component was the style of barrel warehouse. Most in Kentucky are uninsulated, seven-story tin sheds that leave casks at the mercy of the weather. Michter’s opted for more control, building insulated, heated rickhouses with 14-inch-thick walls. They employ “heat cycling” in winter—raising and lowering temperatures in cycles—when most rickhouses lie dormant. (Below about 48 degrees Fahrenheit, the interaction between whiskey and wood all but ceases.) These warehouses are, of course, more expensive to build and operate. They also mimic the ones built by bourbon baron E.H. Taylor at the turn of the century.

Michter’s also looked at another variable, barrel entry proof—the alcohol level of the distillate when it’s put into barrels for aging. In the 19th century, whiskey typically entered barrels at 100 to 110 proof, with 110 being the legal maximum under federal law at the time. In 1962, distillers lobbied to raise the cap to 125 proof, allowing more distillate per barrel and boosting profits. (Some companies were even asking for no cap!) Higher entry proof became the industry norm. Michter’s rolled back the clock, barreling all its products at 103 proof—closer to the old standard. Since barrels contribute a wide range of flavors, and lower alcohol content (read: higher water content) can draw out more flavor compounds from the wood, they believe the extra cost is worth it and might be the reason why the whiskey tastes so rich.

“There are a lot of expensive steps we take,” Magliocco says, “but that’s the single most expensive one. For the same number of bottles, you need more barrels, and you need to build more barrel houses.”

Related: William H. Macy Argues There’s a Right Way to Drink Whiskey: ‘Some People Run Afoul’

The results haven’t gone unnoticed. In just three decades, Michter’s has become one of the most respected American whiskeys, building a devoted following more typical of brands that are centuries old. Michter’s produces two main streams of whiskey: the widely available US*1 bourbons and ryes, and a series of coveted limited releases.

The US*1 line is made with both pot and column stills at the Shively distillery. While there’s no age statement, these whiskeys typically spend five and a half to seven years in casks. They retail for around $50, though barrel-strength editions are occasionally released at a premium.

This year, in Men’s Journal’s Spirits Awards, Michter’s US*1 Kentucky Straight Bourbon was named the best small batch bourbon, while the US*1 Kentucky Straight Rye Whiskey earned the distinction as one of the best whiskeys for old-fashioneds.

Courtesy Michter’s Distillery

In 2019, Michter’s opened a second, smaller distillery at Fort Nelson, in a crenelated 1890 building on Whiskey Row in downtown Louisville. It serves as a visitor center, cocktail bar, and lab, producing whiskey on the original Vendome pot stills Michter’s commissioned in the 1970s. These small runs are double-pot distilled, bypassing the column still, which yields a more neutral spirit.

In 2017, Michter’s also bought a 205-acre farm just over an hour from Louisville, where they grow non-GMO corn, rye, and barley. “The biggest thing I’ve learned is that farming is quite hard,” Magliocco says. The grains are used mainly at Fort Nelson for specialty whiskeys. None have been released yet, but the first of the estate whiskey should reach market in the next year or so.

While the brand’s flagship bourbon, rye, sour mash, and American whiskey have earned loyal fans, its limited releases inspire near-mania. A Michter’s 10-year-old bourbon or rye—once unwanted—now commands $200 or more a bottle, if you can find one. They’re usually released annually, but not always; the master distiller holds them longer if they’re not yet fully mature.

“We’re fortunate to be privately held,” Magliocco says, without shareholders clamoring for regular releases to boost cash flow.

Other limited releases include Shenk’s Homestead Sour Mash and Bomberger’s Declaration Small Batch Kentucky Straight Bourbon, named after the original Pennsylvania distillers. Michter’s Celebration Sour Mash, aged 20 years and first released in 2013, retails for upwards of $4,000 a bottle.

“Whiskey is facing a tough time this year,” Magliocco says. “Distillers have built out tremendous capacity—probably more than necessary.” At the same time, younger generations aren’t embracing spirits with the same zeal as their elders. Tariffs and a Canadian boycott of American whiskey are also taking their toll.

Still, Magliocco says he feels lucky—Michter’s continues to grow, though “not the 20 or 30 percent growth of earlier years.” The company has been more conservative than many in expanding production, leaving it less dependent on moving massive volumes to pay off investments.

“I’m very proud that we can offer accessible whiskeys we really like,” he says. And he believes true whiskey lovers will always seek the best—rewarding the distillery’s aim of making the finest spirit possible.

For Magliocco, whiskey isn’t just a business plan measured in quarters—it’s a craft measured in decades. The market may swell and recede, but barrels keep aging, and he’s betting that care and patience will always find a market. “The industry will have things to work out for a few years,” he says. “But in the long term, it looks bright for American whiskey. More and more people are appreciating it and realizing it can be really high quality.”