His corpse is still warm. The bottle green Oldsmobile in which Jackson Pollock (Wyoming, 1912 – Springs, 1956) was traveling, along with his lover Ruth Kligman – the only survivor – and Edith Metzger, has crashed into the elm trees that flank the straight road that leads to his home in East Hampton, less than a kilometer from the scene of the accident.

It is August 11, 1956, it is 10:15 p.m. on a bright night with a crescent moon. Pollock is 44 years old and drive under the influence of alcohol. The chronicles of the time – like the one published on the cover of the The East Hampton Star on August 16 – narrate how the impact left abundant metal remains and stains on the road. Jackson and his lover were thrown several feet from the car. An ironic way of perpetrating his last dripping: the final stain, that of the sharp impact of his body against the asphalt.

His death symbolizes the closing of an era. He, the last cursed one, the last romantic: the tormented genius who had been blocked for a year, unable to create, crushed by the media pressure of being “the greatest painter in the United States,” according to Clement Greenberg, or of having made, as Piet Mondrian maintained, “the most impressive painting I have seen in a long time.” One day, in 1942, the German painter Hans Hofmann, visiting his studio, asked him if he worked “from nature.” To which Pollock replied: “I am nature”.

Modern history – or, at least, one of its narratives – ends that day. Pollock’s death shocks the entire world. At that time, young Andy Warhol (Pittsburgh, 1928 – New York, 1987) has just turned 28 and lives in New York with his mother, who has moved to take care of him. He is still an advertising illustrator: he works for magazines and department stores such as Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue o Tiffany’s.

That summer he embarked on a great trip with his friend, the illustrator Charles Lisanby, through Asia and Europe. Warhol returns to New York on August 12, the same day that the accident monopolizes the first pages of the newspapers.

Although Warhol and Pollock never met, the former’s admiration for the latter is evident: for his way of reinventing pictorial space and making history. A setting that has nothing to do with the Renaissance or the cinematic.

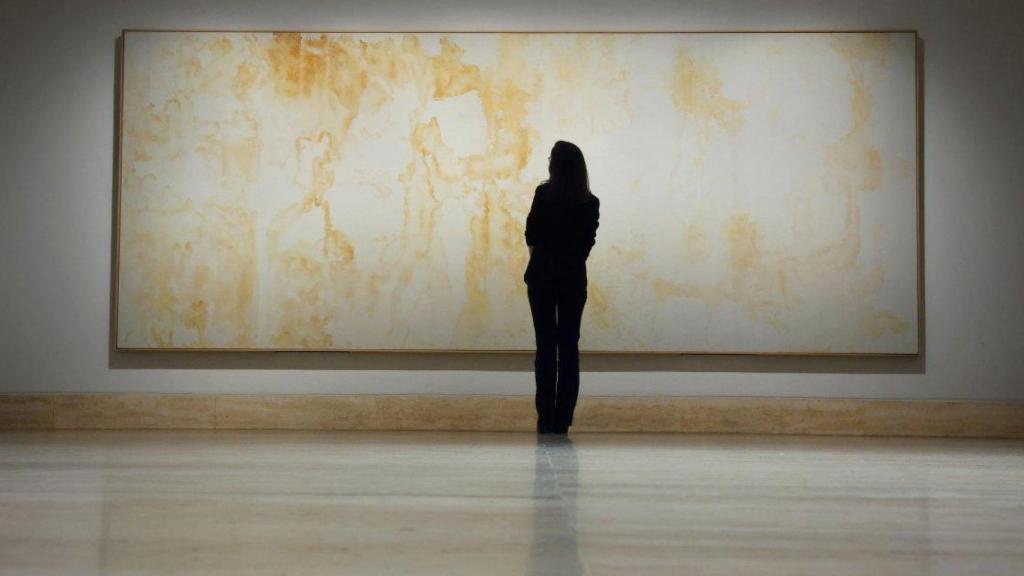

Pollock invents a diagrammatic and continuous painting, without a center, in which each area of the painting weighs the same, organized in flows, forces and gestures beyond the representation. This exhibition is about that: about types of spaces. How a new way of painting creates new and revolutionary pictorial fields and how artists experience that search.

Jackson Pollock: ‘Número 27’, 1950. Foto: The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Vegap / Madrid / 2025

As we tour the rooms, the commissioner, Estrella de Diego, suddenly appears and we take the opportunity to ask her a thousand questions. She tells us, generous and didactic, that with this project she wanted to displace the hegemonic ideas of art history: “that if this artist is conceptual or the other expressionist…, the labels.”

“These artists coincide at one moment, but then they continue their trajectories. Historians tend to order excessively and we have to think that history is a continuum,” says the curator. Combining the painting of Warhol and that of Pollock may seem crazy –two artists with, apparently, nothing in common–, when, in reality, he maintains: “Warhol takes up the place that Pollock leaves open and continually rereads the spatial concept itself.”

“Both painters share much more than we imagine. The space of Western painting is what interests me most in the world; the space of this exhibition is queernot in the LGBT sense, but because it is neither abstract nor figurative, but somewhere in between,” he continues.

The first room shines with a surprising figurative, surreal and tormented Pollock: Untitled (Composition of figures) (1938) anticipates the leap to abstraction. Opposite, two Warhols around Coca-Cola: in Coca-cola (1961) there is still a search, a certain dematerialization; the one from 1962 already shines clearly as a pop icon.

Cy Twombly: ‘Detail of Pan’. 1980. Photo: Fondazione Nicola del Roscio / Rob McKeever / Gagosian

While De Diego details the synergies between these artists, he confesses the difficulty in obtaining most loans: works “guarded like gold” by large collections that have arrived in Madrid with strict protocols. Its fragility suggests that it will probably be the last time that a set of overseas pieces of this magnitude will be exhibited in Europe: its status as a historical exhibition is reinforced.

What we see here are not plagiarisms or genealogies, but rather the same heartbeat, a shared search, the daughter of a time and specific uncertainties. Each artist experiments in his or her own way: for example, Rauschenberg thinks of Warhol and works, like him, from repetition and seriality. But, after Pollock, after his drastic break, how to return to figuration? The conquest was so radical that they only had fragment, superimpose, cross out, plot. There is no turning back.

Marisol: ‘Sin título’, 1960. Foto: Vegap, 2025 / The Museum of Modern Art, New York

These two totems are accompanied by painters who adopted similar methodologies: Lee Krasner – the first canvas of the tour is by Pollock’s widow, who by the way was in Paris during the accident –, Audrey Flack, Anne Ryan, Marisol, Perle Fine, Hedda Sterne and Helen Frankenthaler.

The exhibition leaves us with exquisite pieces. Don’t miss the Pollock with a silver background with pink spots, Number 27 (1950); Sol LeWitt’s fragmented clouds (Clouds1978); los bread details Cy Twombly from the 1980s; Warhol’s electric chairs and a Rothko –Untitled (green on purple), 1971 – dialoguing with the Shadows loaded with Warhol’s pictorial material, which, by the way, They were painted not with brushes, but with mops.

General view of the room. Francis Tsang

The idea of death flies over this story as “the other” spiritual space: from Pollock’s accident to Warhol’s obsession with vanity and the memento mori –skulls, electric chairs, “urine paintings” (1978)–, which surprise some and scandalize others.

After Pollock, Warhol and his contemporaries look for the abstract in the figurative: stains, plots, fragments, new experiments that emerge, overwhelming, in the insignificance of everyday life.

Cover of ‘Tristísimo Warho’l by Estrella de Diego

Trístisimo Warhol

Anagrama reissues, 25 years later and on the occasion of this exhibition, a fantastic essay by Estrella de Diego based on the figure of Andy Warhol. The historian wonders if he was the last heir of the classical tradition, in addition to highlighting certain postmodern syndromes such as melancholy, nostalgia, mythologized death and the concept of glamour. The essay also reads as a zeitgeist of an era and its obsessions, beyond the life and death of the artist. De Diego thus proposes a critical rereading of the hegemonic narratives in the history of art.

The post After Pollock, who’s afraid of Warhol? The Thyssen Museum confronts these two titans of painting appeared first on Veritas News.