The dialogue between engravings, photographs and contemporary digital art installations is the basis of The dream of reason. From the Age of Enlightenment to artificial intelligencethe exhibition that invites us to reflect on how images have been, and continue to be, active tools in the construction of knowledge and the perception of reality.

With this objective they have met at the Telefónica Foundation Space 300 pieces Most of them come from the collection of the University of Navarra Museum and the Fernández Holmann collection.

Among them, stand out a important selection of 18th century engravings —with pieces from the Encyclopedia of Diderot and d’Alembert and the famous series Views of Rome by Piranesi—along with notable examples from the 19th century dedicated to botany, zoology and archaeology, which reached their maximum expression in the imperial edition of the Description of Egypt.

Throughout the journey, engravings and photographs intersect with contemporary installations by Anna Ridler, Quayola, Beauty of Science and ScanLAB Projects, which immerse the visitor in a new way of seeing and knowing the world thanks to technologies such as big dataLiDAR lasers or artificial intelligence.

These tools, trained with large volumes of data and combined with very high resolutions, blur the boundaries between the real, the simulated and the imagined.

Thus, the exhibition police station by Valentine’s Day and Miguelz Ignaciobecomes a conversation between past and present, a dialogue between engravings, photographs and contemporary digital art installations that takes place in thirteen rooms of the Telefónica Foundation Space.

Capture knowledge

The sample tour starts in the 18th centurywhen this impulse to capture reality led artists and scientists to capture it in countless drawings and engravings; images with an encyclopedic vocation, arising mainly as a result of the multiple expeditions undertaken on the five continents.

We are in the Age of Enlightenment and a renewed cultural and scientific curiosity marks in Europe an intense desire to understand and catalog the world, which brings with it the promise of an unprecedented expansion of knowledge.

A paradigmatic example of this enlightened spirit is the Encyclopedia of Diderot and Almbertpublished between 1751 and 1772, which brought together in 28 volumes the knowledge of its time from a critical and secular perspective.

With more than 72,000 articles written by figures such as Rousseau, Voltaire and Montesquieu, the Encyclopedia It addressed topics as diverse as anatomy and astronomy, reflecting the ambition to explain all areas of reality from scientific knowledge. And the first room in the exhibition reflects this.

Albums from the 18th century in room 2. Photo: Fundación Telefónica

Natural fascination

In parallel, the 18th century saw the emergence numerous scientific expeditions that incorporated artists to illustrate natural findings.

Linnaeus laid the foundations of modern taxonomy and his ideas were followed by botanists such as Esenbeck, Trew, Ehret, Rylar and Bateman, who disseminated valuable albums of engravings of plants and flowers that combined rigor and beauty. Other authors offered different approaches, such as Le Vaillant, who defended the direct observation of nature, or Bertuch, who oriented his work towards pedagogical dissemination.

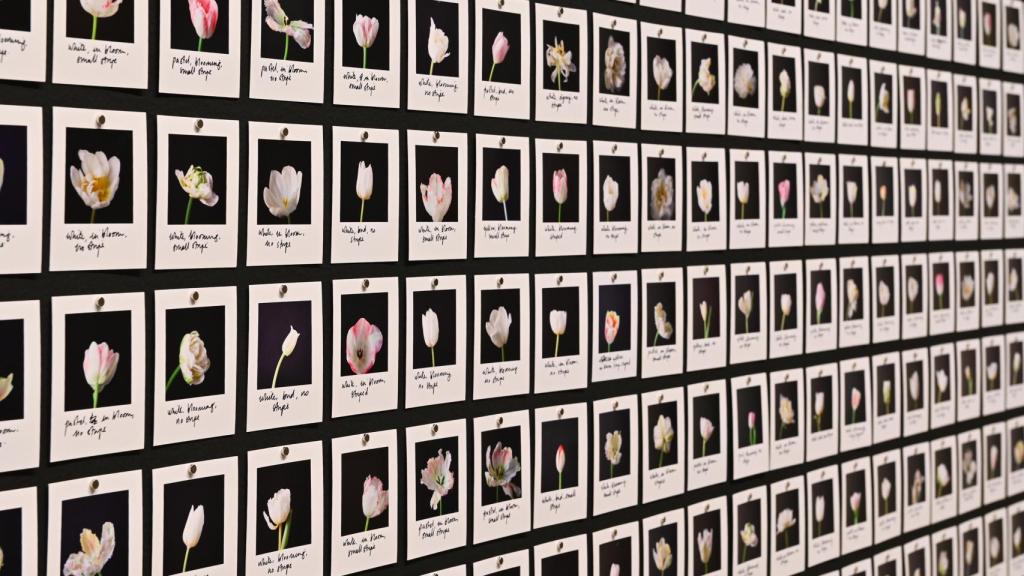

These engravings coexist, in room 3, with the installation Myriad (Tulips) (2018) de Anna Ridlerwhich highlights the human dimension of machine learning by showing how artificial intelligence systems depend on manual work, subjectivity, and human decisions.

Composed of more than a thousand photographs of tulips taken and hand-labeled by the artist, The work reveals the complexity of classifying even seemingly simple elements like a flowerwhile raising questions about biases in algorithms. In this way, it vindicates creativity and human effort against the perception of data as neutral or automatic elements.

Detail of the work ‘Myriad (Tulips)’ (2018) by Anna Ridler. Photo: Telefónica Foundation

Piranesi portrayed her masterfully in his Views of Rome (1748–1774)a series of prints that combine archaeological precision and imagination, anticipating travel photography. This interest in the past also extended to other cultures, as shown by Humboldt and Dupaix, who documented pre-Hispanic civilizations from a scientific perspective, or Laborde and Linant, who visually disseminated Petra.

Piranesi’s engravings, in room 4, dialogue with the work of ScanLAB Projects, an unprecedented tour of Echoes in the light. Fragments of the Roman Forum (2025), using advanced laser scanning technology (LiDAR) to reconstruct it in three dimensions. Like engraving, this process exemplifies technical mastery and deep understanding of reality.

Another of the most relevant milestones of this enlightened spirit, in the context of the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt in 1798, is the Description of Egypt (1809–1823), whose imperial edition can be seen in room 6 of the exhibition. It is an ambitious work composed of 23 volumes that brings together knowledge of the country from Antiquity to the Modern Age.

One of the volumes of the ‘Description of Egypt’ (1809–1823), in room 6. Photo: Fundación Telefónica

Scientists and artists documented pharaonic architecture, mummies, hieroglyphics, zoology and botany with scientific rigor, laying the foundations of Egyptology. The images, accompanied by literary descriptions of the territories, offered a precise and monumental vision of the country which greatly influenced the culture and arts of the time.

The work also became a reference for the development of photographywhich would emerge just a decade after the publication of the last volume.

The natural history engravings from the Description of Egypt —dedicated to fauna, flora and minerals— They talk at the exhibition with the Beauty of Science projectan audiovisual that blurs the boundaries between art and science, showing the hidden beauty of chemical processes through technologies such as macro, micro, high-speed and time-lapse photography, as well as infrared thermal imaging.

in the piece Electrodeposition (2017) it is observed the formation of metal crystals during electrodepositionwhich allows us to see what is happening on scales that escape the human eye.

Photography arrives

In 1839, the appearance of photography revolutionized visual representation. François Arago highlighted its veracity and scientific usefulness, and soon, photographers such as Talbot, Atkins and Lerebours began to explore its possibilities. The daguerreotype gave way to the calotype, allowing the mass reproduction of images and consolidating photography as a means of scientific and artistic documentation.

Photography arrived in Egypt with authors such as Du Camp and Teynard, who captured hieroglyphs and landscapes with unprecedented precision. Later, Frith, Salzmann and Hammersmith explored the eastern Mediterranean, establishing studios in cities such as Cairo and Constantinople. His images, sold to European travelers, consolidated stereotypical iconography of the East.

‘Storms’ (2021), by Quayola, in the last room of the exhibition. Photo: Telefónica Foundation

The photographs of these pioneers dialogue with Storms (2021)an audiovisual installation in which the Italian artist Quayola investigates the tradition of landscape painting, reinterpreted using advanced technologies. Using ultra-high definition images of the raging Cornish sea, the artist generates digital compositions that do not imitate nature, but rather translate it into vectors, intensities and flows of color, and show another way – more abstract and analytical – of representing reality.

The post ‘The Dream of Reason’ brings Piranesi’s ‘Views of Rome’ into dialogue with the algorithm in a formidable exhibition appeared first on Veritas News.