Does any franchise have four great movies in a row? Really think about it. One could argue that maybe there are four back-to-back good Marvel movies, but even there, you’ll find some debate. From Star Trek to Batman, and everything in between, there are very few cinematic powerhouses that have produced two beloved films back to back, much less three. And, four? Unheard of. And yet, on December 9, 1965, when the fourth James Bond film, Thunderball, had an advanced opening in Japan (and later on December 22 and 29 in the U.S. and U.K., respectively), the series proved that, at that time, it couldn’t miss.

Six decades later, not only is Thunderball a near-perfect vintage Bond flick, but it’s also a perfect blend of the cinematic Bond and the literary Bond. And that’s because, even though it was a novel written by Ian Fleming, published in 1961, Thunderball was the first James Bond story to be conceived as a movie first, rather than a book.

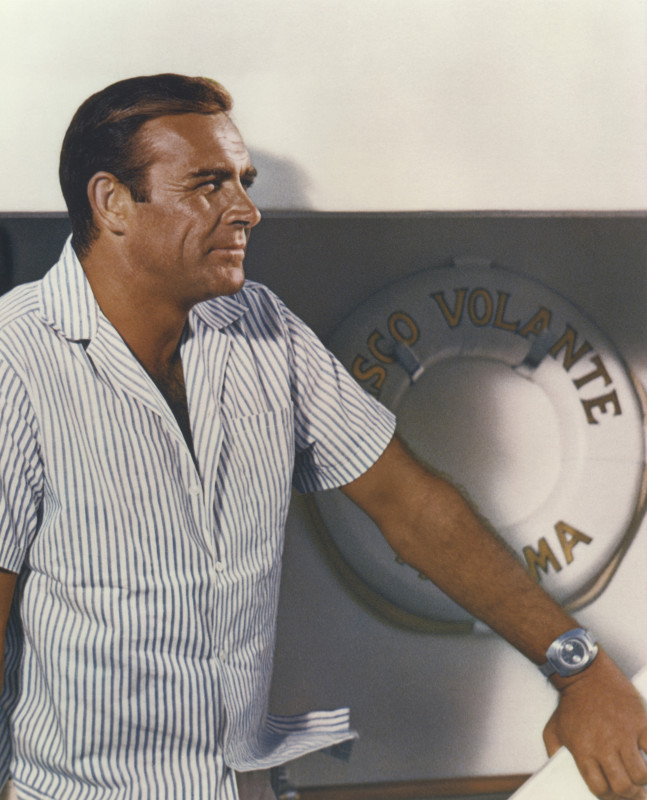

Here’s why, sixty years later, Thunderball remains so unique, and why it still represents the peak of the Sean Connery era of 007.

Thunderball‘s Roundabout Origins

Although there was a brief, one-shot TV James Bond, played by Barry Nelson, in the anthology series Climax! in 1954, the first attempt to create an original screenplay for a Bond feature film began in 1959, when a writer named Ernest Cuneo suggested a story to Ian Fleming about nuclear weapons getting stolen. This eventually morphed into producers Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham essentially collaborating with Fleming to create a screenplay, which, at one point, was called Longitude 78 West, but which Fleming changed to Thunderball, because it was a code word he had heard when he worked in intelligence in WWII.

This was all well before legendary producers Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli launched the now-famous Bond film franchise in 1962 with Dr. No. And, while the Fleming/McClory/Whittingham script didn’t get made, Fleming did write a novel based on it, which was published in 1961. Fast-forward to 1964, Fleming has passed away, EON is prepping the fourth Sean Connery Bond film, and opens up a legal hornet’s nest. McClory had successfully sued Fleming in court for partial royalties to Thunderball, since the genesis of many of the novel’s ideas came from an unmade screenplay, partially developed by McClory. This meant that EON suddenly had to make McClory a major producer on Thunderball if they wanted to get the story made.

And so, after unsuccessfully trying to make a rival Bond franchise, McClory, briefly, became a partner of EON Productions for one of the most memorable Bond flicks of all time.

1965: Bondmania

Getty

At the time of its release, Thunderball was the most expensive Bond movie ever, and also the first filmed in widescreen Panavision. This fact necessitated a new opening gun barrel sequence, in which Sean Connery actually appears as Bond in this iconic moment for the first time. For the first three Bond movies, Connery’s stuntman, Bob Simmons, had appeared as Bond in the gun barrel opening, the distance, and the presence of a hat preventing anyone from realizing it wasn’t really Connery. Thunderball’s gun barrel, though, was new for 1965, and fully featured Connery in the iconic pose, and remains the only one of Connery’s gun barrel moments that is in full color. (Ironically, Connery fights stuntman Bob Simmons in the opening moments of Thunderball, since Simmons plays the elusive Jacques Bouvar.)

The film came at the perfect time, partly because the pop culture “British Invasion” was in full swing, not just in America, but worldwide. And, in a sense, the two most popular U.K. exports in 1965 were The Beatles and James Bond.

The Perfect Formula

With a running time of well over two hours, Thunderball was the biggest and most epic James Bond film up until that point. While Goldfinger had a heist plot and a big climax set at Fort Knox, Thunderball‘s stakes were somewhat higher: the evil organization SPECTRE has hidden two nuclear warheads and intended to detonate them unless a ransom is met. Bond has to track down these warheads in Nassau in the Bahamas, which gives the film a lush, watery vibe that wouldn’t be rivaled in another Bond movie until 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me.

More than any previous Bond film, Thunderball captured Fleming’s love for island living and created a kind of visual travelogue for moviegoers who could never dream of going to places like these islands and living this kind of life. Notably, although some critics complain about the extensive underwater sequences, these moments are pure cinematic innovation. Nobody had done movies quite like this before, and everything, literally, everything, in the film is real.

From Bond’s jetpack in the pre-credits sequence to the very real, live sharks, to the exploding boats, motorcycles, and cars, Thunderball set a high, realistic standard for action movies for the next century. You simply can’t imagine Michael Bay or the Fast and Furious franchise existing without Thundeball coming first. The film embraced the hyberpolic Bond formula set by Goldfinger, but, remained a well-plotted mystery, too. Bond is on the case, the entire time, and the closer he gets to finding the bombs, the more dangerous the film becomes.

Sean Connery has never been funnier, more dangerous, or more charming. And, after this film, he would only star in two more official Bond films, You Only Live Twice (1967), and Diamonds Are Forever (1971). Fittingly, Connery’s only non-canon Bond movie was 1983’s Never Say Never Again, a straight-up remake of Thunderball, led by Kevin McClory. Was this story iconic enough to be filmed twice? When you watch the 1965 original, you can see why nobody would want to let this idea go, no matter who came up with it originally.

When the next James Bond movie finally happens, expecting it to be as good as Goldfinger (1964) or Casino Royale (2006) isn’t quite fair. But we can, and should hope for the spectacle and beauty of Thundeball. James Bond is many things, but the escapist quality, the notion that the viewer is on vacation, is key to the success of the series. And nothing in the Connery era feels quite so completely escapist as Thunderball. This was the moment the classic version of the franchise was at its peak, and it remains, today, an absolute thrill and pure cinematic perfection.